A:

Free speech is one of the most celebrated — and debated — rights in our country. Here’s a primer on what you need to know.

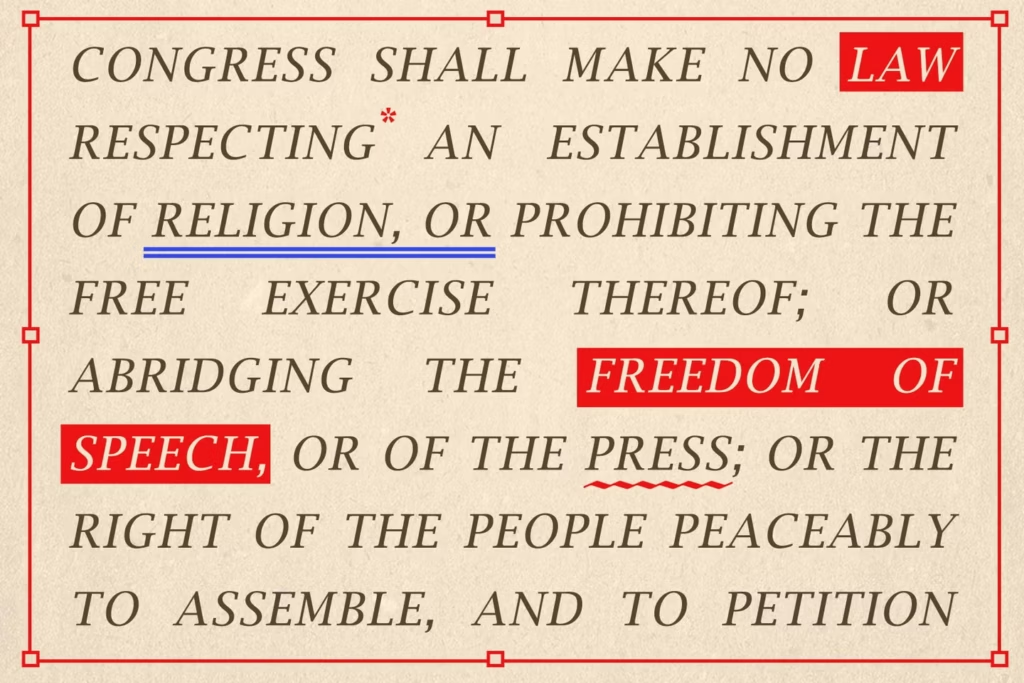

The First Amendment provides expansive Constitutional protections for free speech, but those protections are not unlimited.

First, let’s clarify that the First Amendment protects you from government censorship. The founders of our country enshrined free speech in the Bill of Rights to ensure people could criticize elected officials or people running the government without fear of retribution. This is a cornerstone of American democracy because it makes those in power accountable to the people they’re governing.

Another point of clarification: Speech is broadly defined when it comes to the First Amendment. It encompasses almost any form of expression, including printed materials, broadcast and digital media, visual art, music, theater, films, protests—even clothing with political messages.

What about hate speech?

The Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled that the government cannot restrict speech simply because it is hateful or offensive.

In fact, Justice Samuel Alito wrote in the case Matal v. Tam (2017), “Speech that demeans on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, age, disability, or any other similar ground is hateful; but the proudest boast of our free speech jurisprudence is that we protect the freedom to express ‘the thought that we hate.’”

In other words, the First Amendment doesn’t just protect popular opinions — it protects unpopular and even hate-filled ones, too. As objectionable as this speech might be, the First Amendment prevents the government from becoming the arbiter of what is considered free speech.

That said, there are exceptions to First Amendment protections, and they include:

• Speech that threatens an individual or group and demonstrates intent to harm is not protected. Same thing for speech that incites others to commit imminent violence or other lawless acts.

• Speech that depicts sexual conduct in a way the average person would find offensive and lacks serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value is not protected. Those conditions are known as the “Miller test,” which refers to the court case Miller v. California (1973) that set the standard for what is legally considered obscene.

• Child pornography is never protected under the First Amendment. (New York v. Ferber, 1982)

• False statements that hurt a person’s reputation are not protected, but public officials and public figures must prove that any defamatory statement was made with “actual malice”—or knowing it was false with “a reckless disregard for the truth.” (New York Times v. Sullivan, 1964)

• Speech known as targeted harassment is also not protected. This refers to harassment so severe, pervasive and objectively offensive that the victim is denied equal access to school or work.

Here’s a final clarification: The First Amendment protects you from government censorship, but it does not apply to private organizations. This is often a source of confusion and means employers, private universities or social media platforms may have the right to limit or censor your speech. Your rights online, at school or at your workplace probably depend more on their policy than on Constitutional law.

Bottom line: Free speech is a right but also a responsibility.

The First Amendment offers broad protections to express yourself, but just because you can say something hateful or offensive doesn’t mean you should.

Think before you post.